|

The financial markets have witnessed an explosive growth

in Credit Default Swaps (CDS) over the past few years. The simplest CDS is

essentially an insurance policy against a future credit event, usually

defined as bankruptcy or a failure to pay interest or principal on a debt

security (the reference entity). The

buyer of the vanilla CDS pays periodic (usually quarterly) deal payments to

the seller at the end of every period until the sooner of maturity or

default. If default occurs, the

buyer surrenders the defaulted security to the seller and pays a final

accrual payment. The seller of the

CDS pays nothing to the buyer until default. If default occurs, the seller

is obligated to pay the full notional amount of the swap to the buyer.

The financial literature describes two basic kinds of

models to value CDSs. Structural models start with a company’s

fundamentals, and they are derived from the suggestion by Fischer Black,

Myron Scholes and Robert Merton in their 1973 articles on option pricing

that corporate securities can be valued by the same methods as options.

Structural models, such as CreditGrades™, are attractive because they

provide some insight into the default profile of a particular credit. At

their best, these models are designed to distinguish those firms about to

default or deteriorate from those that are healthy. They are unattractive

because valuations can deviate from those of the actual credit market.

Reduced form models start with actual market debt prices and extract the

default profile implied by those prices. It is assumed that all the market

knows about a particular credit is already contained in the market price.

However, these models do not attempt to explain “why”. Reduced form models

show what “is”, and they accurately show the default implications of

assuming a particular credit spread. The Kynex proprietary CDS Model is a

reduced form model, and the worthiness of one model type over the other

goes far beyond the scope of this article (the JP Morgan Model implemented

on Bloomberg™ is also a reduced form model).

John Hull and Alan White, in their 2000 paper

("Valuing Credit Default Swaps I", University

of Toronto, April 2000), show the CDS spread to be the value that equates the

present value of the expected payoffs with the present value of the

expected deal payments. All discounting is done with interest and

probability of default. Rather than

attempting to determine default and recovery rates directly by sifting

through large volumes of default data (this is the credit agency approach,

e.g. Moody's Investors Service monthly default report), the Hull-White

paper suggests a method of calculating the implied default and recovery

rates from market prices and credit spreads. Default probabilities

measure the frequency of defaults, while recovery rates measure default

severity. The entire spread is assumed to be compensation for purchasing a

risky security (i.e. the liquidity spread is zero), and credit spreads,

default probabilities and recovery rates are linked by the default probability

model. Kynex has implemented a Yield

Spread Model (YSM) and a Present Value Cost of Defaults Model (PVCDM). The PVCDM generates default rates

reflecting the actual term structure of credit spreads, and this model is

really more appropriately used when one is interested in generating CDS

spreads from credit spreads. The YSM (the model most often used in the

market place) is probably more appropriate when a constant credit spread

(rather than a term structure of credit spreads) or a constant CDS spread is

specified. More often than not, our

clients get a constant CDS quote from their brokers to mark their position.

The YSM defines the relationship between risky rates, risk-free rates,

default probabilities and recovery rates in the following way:

Yield Spread

Model

, where , where

the probability of not defaulting (survival)

between the probability of not defaulting (survival)

between

settlement

(time 0) and time n in the future

the recovery rate the recovery rate

the risky yield at time n the risky yield at time n

the risk-free yield at time n the risk-free yield at time n

Note that the cumulative probability of default is

defined as . Given that

spreads are positive, the cumulative probability of default constantly

increases. If spreads and recovery

rates are constant, the force of default will also be constant. . Given that

spreads are positive, the cumulative probability of default constantly

increases. If spreads and recovery

rates are constant, the force of default will also be constant.

Although numerically close in value (according to

theory), CDS spreads and credit spreads are really quite different fundamentally. Kynex shows the credit spreads

corresponding to a constant CDS spread on its main

output screen. Although

usually close in value, actual market credit spreads can deviate from

market CDS spreads. Please refer to

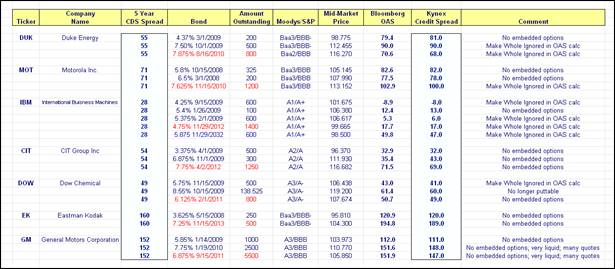

the chart below which compares CDS spreads and credit spreads for some well

known, liquid credits on 4/22/2004.

Probabilities of default and recovery rates are the

prime determinants of CDS spreads, while credit spreads are influenced by additional factors such as the

existence of embedded options, time to maturity, difference between the

bond coupon and the currently offered coupon on new issues of similar

bonds, liquidity and tax treatment.

Generally speaking, a bond with embedded options will trade wider

than a similar bond without contingent flows (even on an OAS basis). Because of price compression, a bond

trading at a high premium usually will trade at a wider spread than one

with a coupon closer to currently issued bonds (e.g.MOT 7.625% 11/15/2010

and DOW 8.55% 10/15/2009). Given the

shape of the yield curve, one would expect longer securities to trade wider

than shorter ones (e.g. IBM 5.875% 11/29/2032).

Although CDS spreads may give an initial idea of where credit spreads are, one should not blindly assume that the

credit spread is identical to the CDS spread (the unusually tight

spreads on the IBM bonds maturing in 2009 truly existed on 4/22/2004, and

were caused by demand issues rather than fundamentals). In a 2003 paper by Francis Longstaff,

Sanjay Mithal and Eric Neis (“The Credit Default Swap Market: Is Credit

Protection Priced Correctly?”), the authors suggest that the CDS market

leads the corporate bond market by at least a week. They go on to suggest that the CDS market

even appeared to precede the equity market for a sizeable fraction of the

firms in their sample.

The CDS market has grown dramatically in size and

complexity. According to the ISDA,

the notional amount on credit derivatives reached $2.69 trillion by the

middle of 2003 (as compared to an outstanding volume of $123.9 trillion for

vanilla interest rate derivatives).

That is up 25% since the end of 2002, and it is the fastest growing

sector of the derivatives market.

The complexity of CDSs has grown because of financial (e.g.

diversification) and regulatory (e.g.

capital adequacy requirements) considerations. Once again, the

proliferation of various types of credit derivatives goes far beyond the

scope of this paper, but it is important to note the marriage of credit derivatives

with securitization. The credit risk in a portfolio can be bundled (into a

basket), tranched (using a Collateralized Debt Obligation) and sold in the

capital markets like any other security. CDO tranches can have vastly

different risk characteristics than their underlying assets (which might

also include single name or basket CDSs).

Valuation Model Comparison

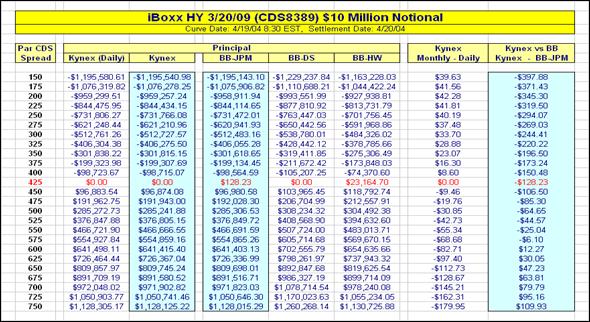

It is instructive to use an outstanding CDS in the

market to evaluate the Kynex proprietary model. The following chart uses a

$10 million notional iBoxx High Yield CDS with a 425 deal spread and

maturing on 3/20/09. The chart shows

the principal values resulting from sweeping the market CDS spread from 150

to 750. The columns labeled

“BB-JPM”, “BB-DS” and “BB-HW” show the values corresponding to the

Bloomberg™ implementation of the JP Morgan model, the Discounted Spreads

model and the Hull-White model, respectively.

The column labeled “Kynex (Daily)” shows what we believe

to be the most accurate values.

These values are calculated by evaluating the expected payoff

integrals on a daily basis. The

amount of CPU time required forbids us from making this option available on

our calculator screen. Instead, expected

payoffs are evaluated monthly, and then adjusted to approximate the daily

values. These values are shown in the column labeled “Kynex”, and the

difference between the monthly and the daily values are shown in the next

to last column. The Bloomberg™ JP

Morgan model is probably the most widely used model in the marketplace, and

differences from that model and the Kynex model are shown in the last

column. Apparently, Bloomberg’s JP

Morgan model seems to have a small problem, which can be seen when the

iBoxx CDS is valued at the current deal spread of 425. Both models give good valuations.

Recent Model Enhancements

The Kynex model was first released in December of

2002. Recently, the model and its

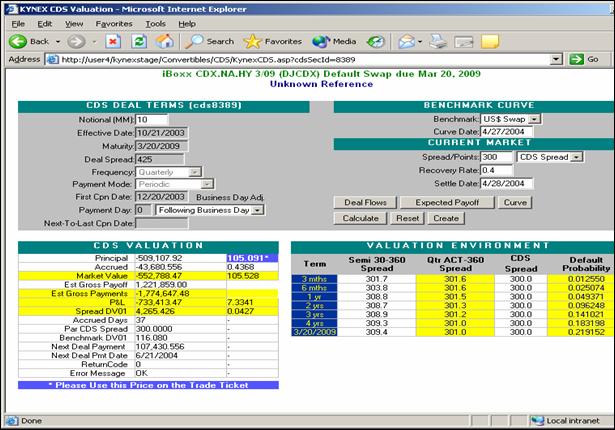

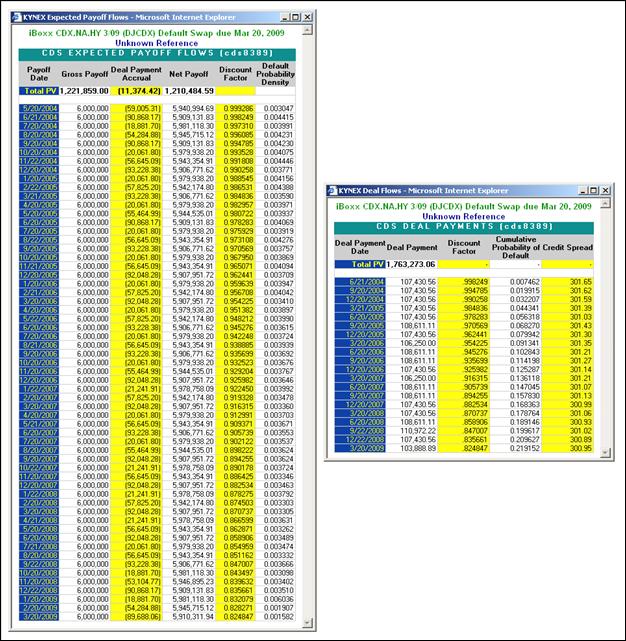

corresponding valuation screen have been updated. In addition to the main screen, Kynex

also shows the deal payments and

the expected payoffs in separate windows.

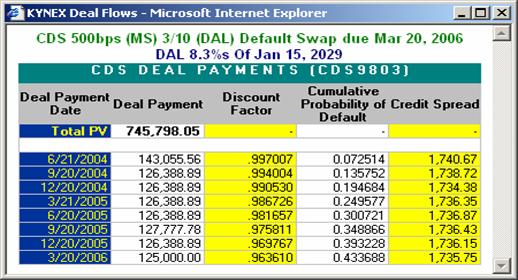

The deal payments screen shows the value and timing of

every future payment from settlement. Additionally, the first line shows

the total expected value of the future payments on settlement discounted

with interest and default assuming that all deal payments are made. The

expected payoff flows include the regular payoff due at default plus the

accrued interest on the deal payment.

The gross deal payments total present value includes this extra

accrual piece (1,774,647.48 = 1,763,273.06 +

11,374.42). On the expected

payoff flows window, the column labeled “Default Probability Density” shows

the probability of not defaulting (survival) from settlement to the prior

payoff date shown, and then defaulting before the current date. For example, the probability of surviving

from 4/28/2004 until 6/21/2004 and then defaulting before 7/20/2004 is

0.003991 as shown below.

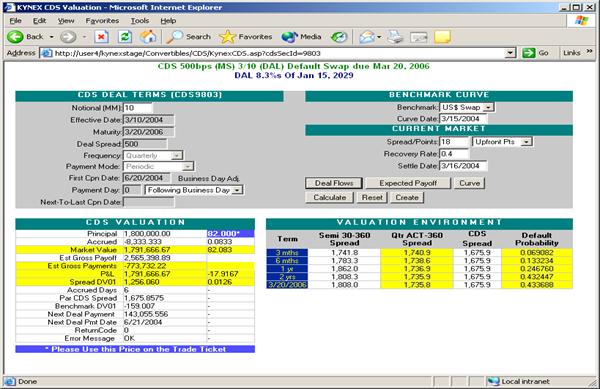

On the main input and valuation window, fields now exist

to accommodate odd first and last deal payments as well as business day

adjustments. All dates should be entered unadjusted for business days. If the CDS requires business day

adjustments, the model will adjust the dates. The “Payment Day” field

(usually the day of the unadjusted first deal payment date) is crucial to

maintaining the cycle of the CDS payments. If these values are not

specified, the model will make assumptions which may or may not be

appropriate depending upon the specific CDS contract. When creating single

name CDSs with the “Create” button, it is easier to first go to the Kynex

Detail Screen and click on the “CDS Valuation” link. We also suggest you enter all of the

necessary terms and do a calculation before clicking on the “Create”

button. The terms on the creation

page will automatically be filled in, thus reducing input errors. It should be noted that all iBoxx CDSs

are already in Kynex. There is no

need to enter them again. If you wish to see a list of all the iBoxx’s,

just do a search on “CDX” from the Kynex search box. If you know the Bloomberg™ deal number,

that value can be placed in the search box for immediate access. If you want to identify the counterparty,

just click on “Trade History View” from your portfolio. Currently, Kynex

portfolios and Trade Entry administer long protection as being short the

credit. CDSs should be marked in bond price terms in Trade Entry. However,

existing CDSs in portfolios must be marked by placing the market CDS spread

in the “Convert Price” or the “Convert Anchor” column (depending upon the

view). For those clients using Kynex Trade Entry, your ticket price is

always high-lighted in blue on the valuation screen. As a reminder, if you are long

protection, the Trade Entry ticket should be “sell short”. If you bought a

$10 million notional CDS, the quantity should be 10,000 (like a bond). If you sold protection, the Trade Entry

should be “buy long”. At unwind, the

ticket should be a “buy cover” if long protection, and “sell long” if short

protection.

As the liquidity of the CDS market grows, more of our

clients are buying and selling existing CDSs. This means that the deal spread is

usually not equal to the market CDS spread, thus requiring an upfront

payment. Rather than being quoted on

a CDS spread basis, some of our clients get quotes based on upfront bond

points. The updated CDS calculator

now accommodates these quotes. Please refer to the screens below.

Suppose you sell $10 million notional, two year

protection on DAL 8.3% 1/15/2029, and the terms are quoted as 18 points

plus 500 running. The seller then collects $1,791.666.67 ($1,800,000 less

accrued) upfront plus the future deal payments. The equivalent CDS spread

is 1675.8575. iBoxx CDSs can also be

quoted as a short bond price, and these quotes can be directly entered into

the Kynex valuation screen by choosing “Sh Bond Px” next to the

“Spread/Points” input field. Upfront

points are the complement of the short bond price.

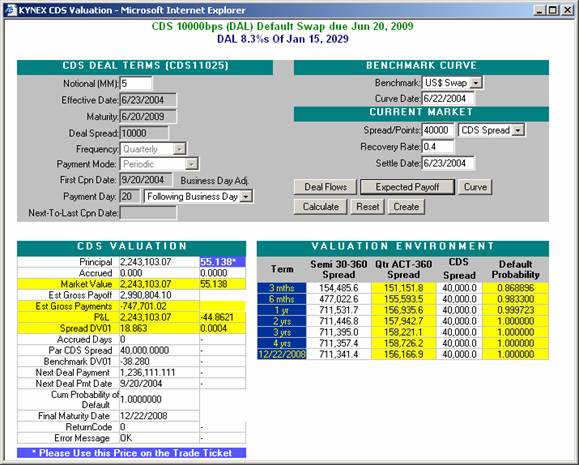

Investment grade names are no longer the only candidates

for CDS protection. As a credit

nears bankruptcy, the credit spread will balloon. If the term of the CDS is long enough and

the market spread is high enough, the cumulative probability of default

will approach certainty. If the spread is extraordinarily high, Kynex will

terminate the CDS before maturity at the point where the cumulative default

probability reaches one. Please refer to the screen immediately below.

At a market spread of 40000, the default is certain by

12/22/2008. Please note that the recovery rate should not be lowered

artificially. Theoretically at least, the frequency and severity of default

are independent. Please note that this functionality should not be used to

evaluate those CDO tranches (especially the equity piece) that absorb a

disproportionate amount of asset loss.

Reduced form models are intended to identify the default profile of

a credit. Evaluating a CDO equity tranche with this tool says nothing about

the underlying default performance of its assets or the trust structural

definitions and rules. Kynex does not currently have a structuring tool to

properly front-end these kinds of securities.

Another significant enhancement to the Kynex model is

how single premium CDSs are evaluated. Most market participants currently

use a periodic payment calculator for both single risky and single

risk-free contracts. For single

risky contracts, the market value is defined as the gross payoff of the

corresponding periodic payment CDS.

For single risk-free contracts, the valuation becomes more

convoluted. In addition to the

regular payoff of the periodic payment CDS, the buyer of the single

risk-free contract is entitled to a refund calculated as the present value

of the future deal payments. These refunded deal payments are based on the

original deal spread, and they are discounted without taking into

consideration the probability of default (discounted with interest only).

The initial single premium is calculated as the present value of the deal

payments of the corresponding periodic payment CDS. In order to value the single risk-free

unwind, market participants enter a 0 as the market CDS spread, and the

current CDS spread for a periodic payment CDS is entered as the deal spread

(the Bloomberg™ CDS calculator will not take a zero market spread, so

market participants place a one in the market spread and one plus the

current spread in the deal spread).

Kynex has rejected this methodology.

Instead, we have gone back to first principles by evaluating the

true expected default payoffs in the future.

Our main reason for taking this approach is to correctly

identify the risk characteristics of the single premium CDS. For purposes of illustration, assume that

the iBoxx High Yield CDS mentioned above has been sold on a single risky

basis. Please refer to the chart

below.

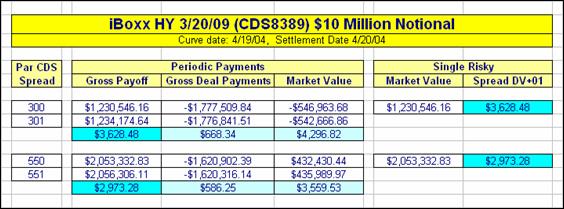

Both the periodic payment and the single risky contracts

were valued at a 300 and a 550 spread. As you can see, the Spread DV+01 of

the periodic payment CDS is not equal to that of the single premium. At

300, the periodic payment CDS has a total Spread DV+01 of $4,297, while the

single risky contract has a DV+01 of $3,628. Since

deal payments are not being made, the single risky has a smaller Spread

DV+01. Market participants think

of the CDS Benchmark DV+01 as being almost zero. For periodic payments CDSs, this rule of

thumb is accurate. It is less

accurate for single premium CDSs.

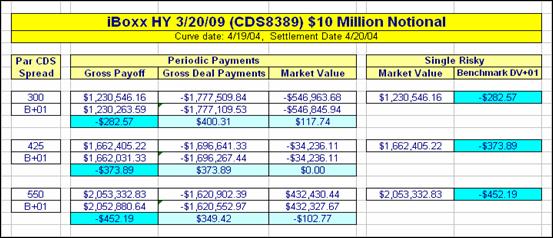

The chart shown below compares the Benchmark DV+01 of the same CDS

used above on both a periodic payment and single risky basis.

During our evaluation of the single risk-free contract,

we also noticed an inconsistency in how that contract is defined. The additional refund at default is

calculated on the basis of the initial deal spread, while the unwind is

calculated on the basis of the current market spread. This disconnect results in improper

unwind values as currently defined by the market.

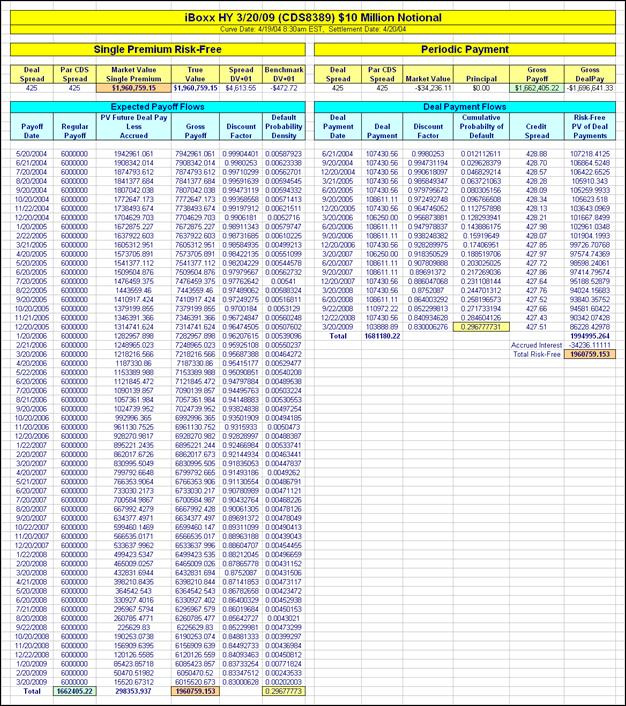

It is instructive to view the expected payoff flows when

the current spread is equal to the original deal spread of 425. Please see the first

table below in which the single premium risk-free expected

payoff flows are compared to the equivalent periodic payment deal payment

flows when the market CDS spread is 425.

As expected, the single premium (market value) of the single

risk-free CDS is equal to the risk-free present value of the periodic

payment deal payments. Note also

that the single risk-free single premium is equal to the discounted (with

interest and default) gross payoff. When the market spread is equal to the

deal spread, the true value is identical to the single premium.

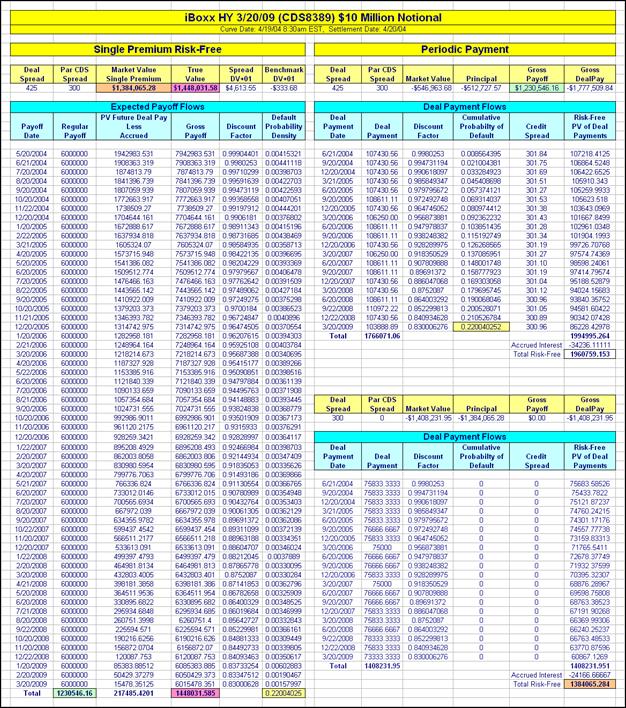

However, if the single risky CDS is valued at a 300 CDS

spread, then the true value diverges from the unwind single premium as

currently calculated in the marketplace.

Please see the second table

below in which the flows are evaluated at a market CDS spread of 300. Note that

the single risk-free true value is still equal to the discounted (with

interest and default) gross payoff.

Note that the risk-free gross payoff values at every future date are

identical (except for a small adjustment used to approximate daily payoffs)

regardless of the market CDS spread. However, the single premium is now

erroneously based upon deal payments of a 300 spread. In this case, the true value exceeds the

single premium by $63,966. The

seller would pick this up at unwind.

But this inconsistency cuts both ways. In the last

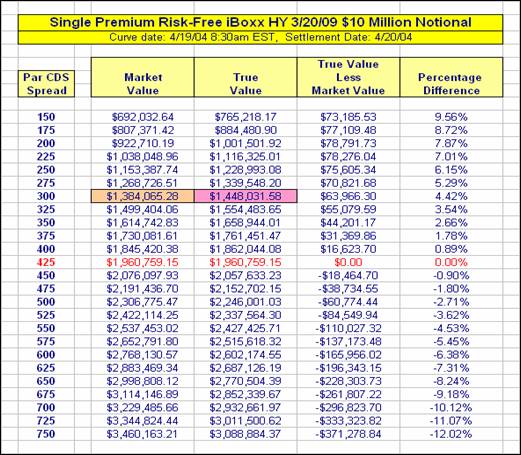

table found below, we quantify the difference between the market

value and the true value by once again sweeping the market CDS spread from

150 to 750. At a 300 market spread,

the seller picks up 4.42% of the true value, but at 500 he gives up 2.71%. Our conclusion is that the single

risk-free contract as it is currently administered is stacked in favor of

the seller. If the credit in

question improves, so that the buyer is more likely to unwind, the seller

gains from the unwind. If the credit

deteriorates, the seller will be hit with more of a loss if an unwind

occurs. However, the buyer would not

have the incentive to unwind under that scenario.

|